Forget factories. There is a better answer to the continent’s jobs crisis

June 26, 2025 | Nairobi

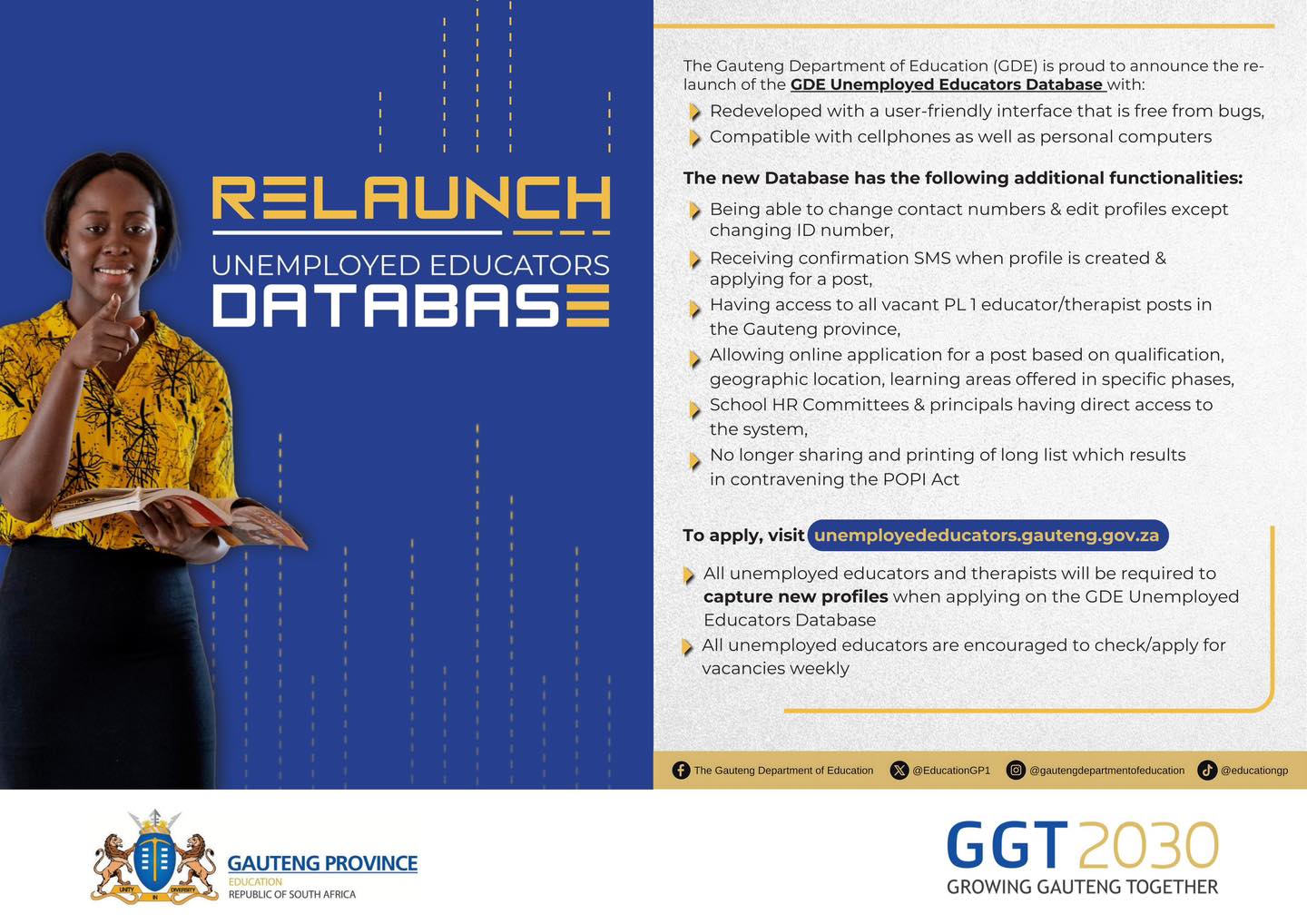

Mercy Mugure first heard about business-process outsourcing (BPO) in the mid-2000s. Word of how the practice was transforming India, its global champion, reached Africa, which had largely missed out on the fruits of globalisation. “We thought: why not us?” says the Kenyan entrepreneur. With a friend, she set up one of Kenya’s first BPO firms in 2006, hoping to tap into the job-creating potential of an industry that covers anything from picking up phones and processing insurance claims to flagging illegal or violent content on social media.

Today Ms Mugure’s company, Adept Technologies, remains something of an exception. Policymakers’ hopes that Africa would replace India and the Philippines as the world’s back office have not been realised. Yet things may be changing. As increasing demand for workers to train algorithms and annotate digital data brings a boost to the industry, a growing share of the work in the coming years is expected to be done by Africans.

The jobs are sorely needed. Three-quarters of young Africans report they cannot find adequate work. Traditional manufacturing, which helped spur growth by providing mass employment in countries such as South Korea and Vietnam, requires ever more complex machinery but ever fewer humans to operate it, making it less useful as a source of plentiful good-quality jobs.

Outsourcing could fill some of that gap. Currently just 1m Africans work in BPO, about 2% of the industry’s global workforce. Yet between 2023 and 2028 the industry is expected to grow by around 14% a year in Africa, nearly twice as fast as the global BPO growth rate of 8% and four times Africa’s annual growth rate, which the World Bank expects to reach 3.5% this year. In Kenya, which hosts some of the world’s largest outsourcers, the BPO growth rate is projected to be even higher, at 19%, according to Genesis Analytics, a consultancy. “Africa is the next frontier,” says Martin Roe, chief executive of CCI Global, whose newest call centre in Kenya seats 5,000 workers.

Anglophone Africa, in particular, has always had some advantages in attracting BPO firms. Its youthful population is increasingly well educated, with strong English-language skills. Bosses claim many Western customers prefer the sound of what they say are more “neutral” African accents to those of Indian English-speakers. The continent’s time zones are convenient for businesses in America and Europe. In the past, all that was not enough to tip the scales away from Asia. Yet this time may be different.

One factor is labour-cost arbitrage, notes Mark Graham, co-author of “The Digital Continent”. Wages and other costs in Kenya are 60-70% lower than in America, Europe and Australia. Workers in India and the Philippines, meanwhile, are getting richer, and therefore more expensive to hire. The Fairwork project at Oxford University, which evaluates tech companies’ work standards, found workers at a foreign BPO firm in Kenya made $233 a month. Their peers at a comparable company in the Philippines earned $284.

More targeted sweeteners from governments help, too. Kenya’s long-awaited national BPO policy, due to be unveiled in July, aims to create 1m jobs in the sector over the next five years. Nigeria launched its “Outsource to Nigeria” scheme in 2024. Both offer generous tax breaks and subsidies; South Africa’s even doles out cash grants for new jobs. “You have to incentivise the sector deliberately,” says John Kiria, Kenya’s digital-economy tsar.

Structural changes in the global economy also work in Africa’s favour. With labour forces in many parts of the world shrinking, demand for African labour is growing. In May the German government hosted an event in Berlin that aimed to connect German and European companies with African BPO firms.

The BPO boom is not a panacea. Critics are concerned about the quality of new BPO jobs, especially in content moderation for social media and annotation for artificial intelligence (AI). Workers complain of being forced to stare at disturbing text or images without adequate psychological support, or perform monotonous tasks without sufficient breaks. In Kenya former moderators have sued Meta, a social-media giant, and Sama, a Californian BPO company briefly hired by Meta, over working conditions. (Sama denies wrongdoing and says it no longer offers content moderation. Meta argues Kenyan courts do not have jurisdiction and that the complainants were not employed by Meta itself.)

A related issue is hyper-mobility. Faced with negative publicity or tricky governments, companies at the top of a BPO supply chain can go elsewhere. A recent investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, a London-based outfit,found that Meta had quietly moved its content-moderation work from Kenya to Ghana following litigation in Kenya. (Meta says it chose to keep the new location secret to protect clients and the moderators themselves, and that it takes the support of moderators seriously.) “For the client, it’s an overnight decision,” says Mr Kiria. “By tomorrow morning, 8am, they’re in India.”

The biggest challenge is AI. Many basic tasks have already been automated. A decade ago Graham Parrott, a British entrepreneur, founded one of Ethiopia’s first BPO firms, which closed during the pandemic. Now he fears the country “may have already missed the boat”. Bobby Varanasi, a consultant, argues that the industry is being “completely hollowed out at the bottom”. A report by Genesis Analytics for the Mastercard Foundation estimates that more than 40% of tasks in the BPO industry in Africa are at risk of automation.

But tasks are not the same as jobs. Wendy Gonzalez, the boss of Sama, says that when the company set up in Africa in 2008, data labelling meant answering questions like “Is there a cat in this photo?”. These days it involves more sophisticated tasks, such as ensuring that writing suggestions from AI models are grammatically correct. Mr Roe of CCI argues that there will be continued demand for more “complex and emotional” services only humans can deliver. Such work could be better paid.

That means that in the long term, gaining a bigger share of global outsourcing may ultimately be about securing the highest-value jobs. Ms Mugure of Adept Technologies does not offer content moderation. Instead, she is looking to expand into “knowledge-based work”, which will require more Kenyan graduates trained in AI and computer science. For governments, investing in education may be the best hedge against being left behind.

Image:mg.co.za